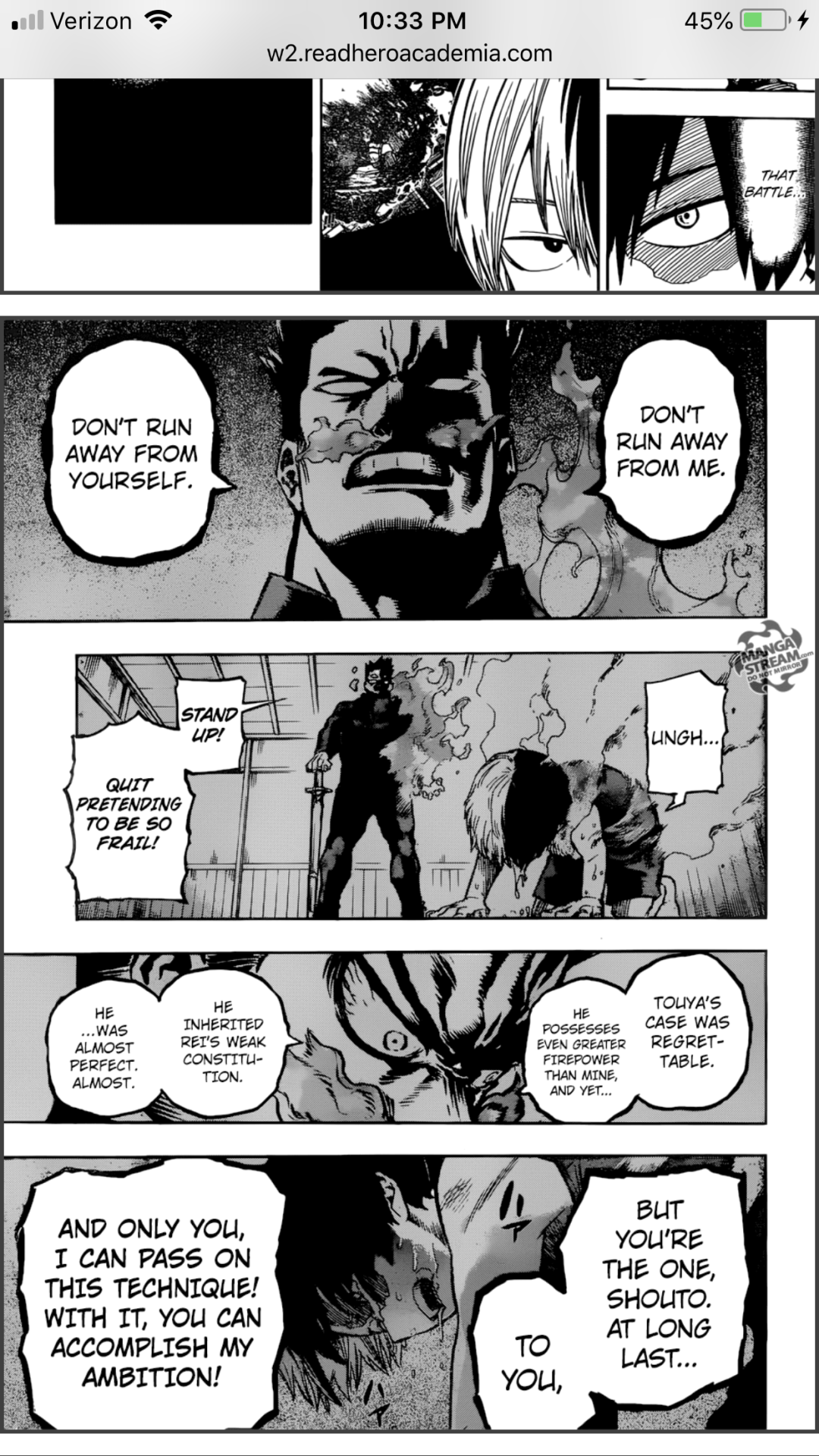

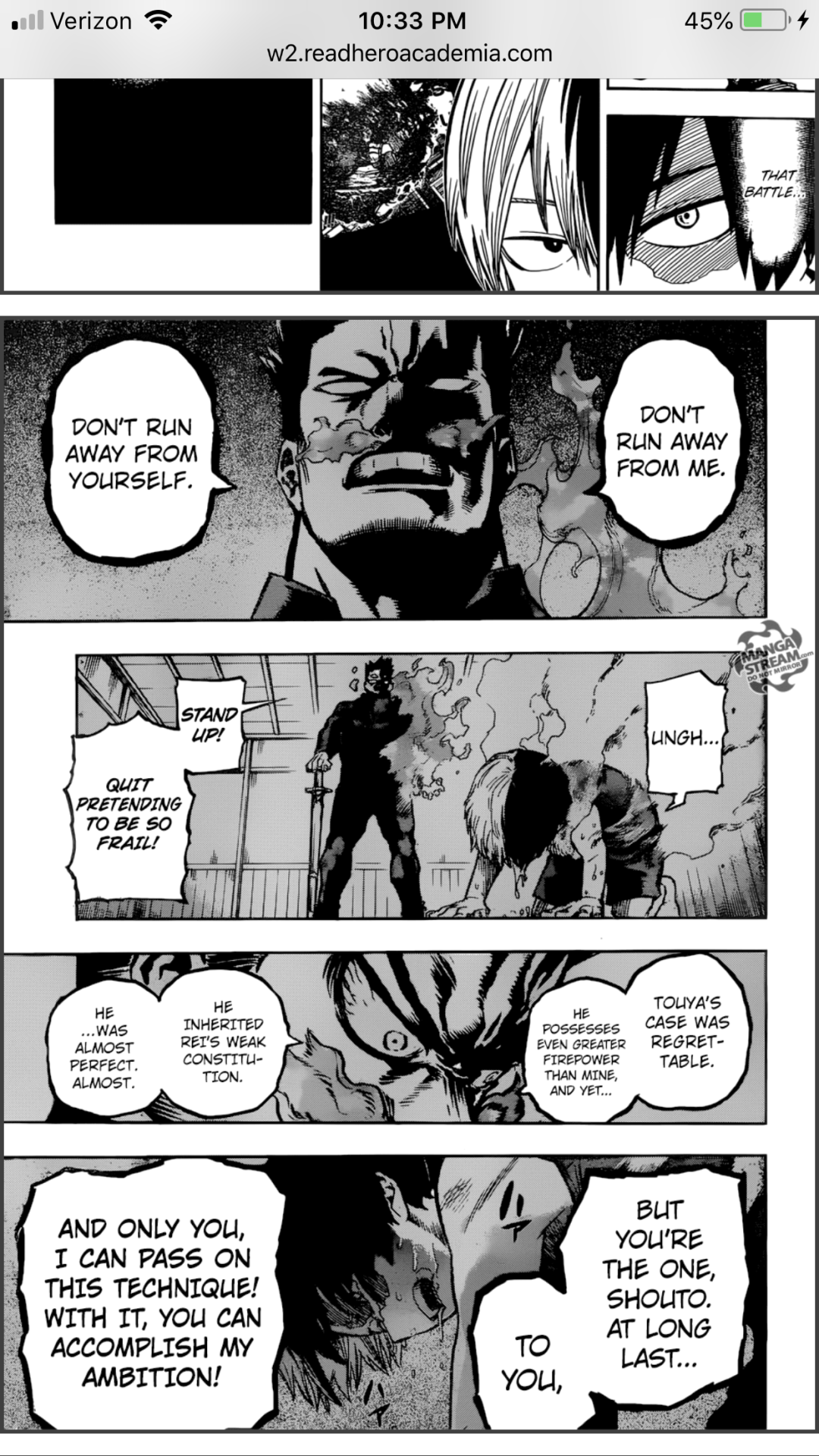

the more i learn about endeavor the more i hate his fucking guts

the more i learn about endeavor the more i hate his fucking guts

I’ve been living with the effects of complex trauma for a long time, but for many years, I didn’t know what it was. Off and on throughout my life, I’ve struggled with what I thought was anxiety and depression. Or rather, In addition to being traumatized, I was anxious and depressed.

Regardless of the difference, no condition should ever be minimized. If you are feeling anxious or depressed, it’s important and urgent to find the right support for you. No one gets a prize for “worst” depression, anxiety, trauma or any other combination of terrible things to deal with, and no one should suffer alone. With that in mind, there is a difference between what someone who has Complex PTSD feels and what someone with generalized anxiety or mild to moderate depression feels.

For someone dealing with complex trauma, the anxiety they feel does not come from some mysterious unknown source or obsessing about what could happen. For many, the anxiety they feel is not rational. General anxiety can often be calmed with grounding techniques and reminders of what is real and true. Mindfulness techniques can help. Even when they feel disconnected, anxious people can often acknowledge they are loved and supported by others.

For those who have experienced trauma, anxiety comes from an automatic physiological response to what has actually, already happened. The brain and body have already lived through “worst case scenario” situations, know what it feels like and are hell-bent on never going back there again. The fight/flight/ freeze response goes into overdrive. It’s like living with a fire alarm that goes off at random intervals 24 hours a day. It is extremely difficult for the rational brain to be convinced “that won’t happen,” because it already knows that it has happened, and it was horrific.

Those living with generalized anxiety often live in fear of the future. Those with complex trauma fear the future because of the past.

The remedy for both anxiety and trauma is to pull one’s awareness back into the present. For a traumatized person who has experienced abuse, there are a variety of factors that make this difficult. First and foremost, a traumatized person must be living in a situation which is 100 percent safe before they can even begin to process the tsunami of anger, grief and despair that has been locked inside of them, causing their hypervigilance and other anxious symptoms. That usually means no one who abused them or enabled abuse in the past can be allowed to take up space in their life. It also means eliminating any other people who mirror the same abusive or enabling patterns.

Unfortunately for many, creating a 100 percent abuser-free environment is not possible, even for those who set up good boundaries and are wary of the signs. That means that being present in the moment for a complex trauma survivor is not fail-proof, especially in a stressful event. They can be triggered into an emotional flashback by anything in their present environment.

It is possible (and likely) that someone suffering from the effects of complex trauma is also feeling anxious and depressed, but there is a difference to the root cause. Many effective strategies that treat anxiety and depression don’t work for trauma survivors. Meditation and mindfulness techniques that make one more aware of their environment sometimes can produce an opposite effect on a trauma survivor. Trauma survivors often don’t need more awareness. They need to feel safe and secure in spite of what their awareness is telling them.

At the first sign of anxiety or depression, traumatized people will spiral into toxic shame. Depending on the wounding messages they received from their abusers, they will not only feel the effects of anxiety and depression, but also a deep shame for being “defective” or “not good enough.” Many survivors were emotionally and/or physically abandoned, and have a deep rooted knowledge of the fact that they were insufficiently loved. They live with a constant reminder that their brains and bodies were deprived of a basic human right. Even present-day situations where they are receiving love from a safe person can trigger the awareness and subsequent grief of knowing how unloved they were by comparison.

Anxiety and depression are considered commonplace, but I suspect many of those who consider themselves anxious or depressed are actually experiencing the fallout of trauma. Most therapists are not well trained to handle trauma, especially the complex kind that stems from prolonged exposure to abuse. Unless they are specially certified, they might have had a few hours in graduate school on Cluster B personality disorders, and even fewer hours on helping their survivors. Many survivors of complex trauma are often misdiagnosed as having borderline personality disorder (BPD) or bipolar disorder. Anyone who has sought treatment for generalized anxiety or depression owes themselves a deeper look at whether trauma plays a role.

damn, this is important!

I have CPTSD and I really feel this. I have had many frustrating, shitty experiences with mental health professionals that will barely acknowledge my serious mental health issues mostly come from complex trauma.

They don’t know how to deal with it, they treat it like regular anxiety and depression, and when it doesn’t work, it makes me feel like I’m too fucked up and too far gone.

ohhh

ohhh man

We Can’t Keep Treating Anxiety From Complex Trauma the Same Way We Treat Generalized Anxiety

There’s nothing free about non-commitment rooted in intimacy avoidance. There’s nothing free about polyamory emanating from unresolved trauma history. There’s nothing free about wanderlust sourced in relational terror. Being a ‘free spirit’ has its place- as part of the exploration of self, other, ways of being- but if it’s emanating from woundedness, it’s just another prison. Our defenses can trick us into believing that our hunger for freedom is fundamental to our soul’s imprint, but it’s often something else. It’s often an ungrounded flight of fancy, a delay tactic, a hide and seek game we are playing with our pain. If we avoid closeness, we can fool ourselves into believing that we have healed. But it only works for so long. Because we aren’t healed, and the remnants of our unresolved pain will show up everywhere. Simply put, we are wounded in close relationship, and some part of our healing has to happen in close relationship. There’s no way around it. The best way to free ourselves from pain-body prison is to learn how to trust again.

trauma doesn’t often feel like trauma is ‘supposed’ to feel. it feels like indifferent detachment, watching from outside yourself because nothing can hurt you there. it feels normal, just how people interact, so why are you making a big deal about it? it feels like a joke – just how kids play, just how adults tease, just how some relationships work.

you wake from nightmares five years later and still wonder if you made it all up.

trauma can look like bad behaviour. like the stubborn refusal to get better, to stop self-destructing. trauma is putting yourself in harm’s way because you don’t really mean it, or because it’s funny, or because you just want to feel something, or because you just want to stop feeling. it’s wanting to destroy and reassemble yourself into another person entirely, so your real life can begin. because this isn’t real. because really bad things don’t happen to people like you.

trauma is the constant feeling of being an impostor. it’s the drive to survive twinned with the impulse to make yourself more sick in more ways. to hurt yourself to prove how bad you feel, or to punish yourself for exaggerating. you want people to believe what you’ve been through, to tell you your feelings are real, that your memories really happened. but when people do take you seriously, you play it off as a joke, apologize for bringing the mood down.

you go on and on about how it wasn’t that bad. you seek permission to still love the ones who hurt you, because it’s the people closest to us who can hurt us most deeply.

you can feel like the people who hurt you are the only ones who really knew you. in low self esteem, you can mistake cruelty for honesty.

there will always be people who have been through worse. that doesn’t make what happened to you okay.

there will always be people who don’t believe you. that doesn’t mean you are lying.

at some point, you have to take yourself seriously. you have to make a life you can stand to live. it’s the only way to survive.

for the record, ‘not feeling anything’ is a valid and not unusual response to trauma or grief

so if you feel empty and devoid of feeling, it’s not because you’re a cold and uncaring person.

Sometimes, not feeling anything is the only way you can cope.

Be prepared for a delayed reaction, too. It’s very common to be totally calm during a crisis, and then days or weeks (or years) later suddenly get hit with a tidal wave of “HOLY SHIT THAT HAPPENED.”

Sometimes your mind waits until it feels safe to start processing things emotionally. It’s a powerful survival strategy, but it can really blindside you, because just as you start to feel like things are okay, you’re overwhelmed by the realization of how not-okay things were before.

This may not happen, and that’s okay too. But it’s something to watch out for when your initial reaction is numbness.

It’s also okay to have seemingly inconsistent reactions sometimes, or reactions that seem contrary, especially if you’re exhausted or in shock. Be open to how you feel, and accept it.

*applause* you guys know what’s up

kai cheng thom, from her collection a place called no homeland

In her book Trauma and Recovery,

Judith Herman writes about forgiveness (in the context of atrocities and abuse):

“Revolted by the fantasy of revenge, some survivors attempt to bypass their outrage altogether throught a fantasy of forgiveness. This fantasy, like its polar opposite, is an attempt at empowerment. The survivor imagines that she can transcend her rage and erase the impact of the trauma through a willed, defiant act of love.

But it is not possible to exorcise the trauma, through either hatred or love. Like revenge, the fantasy of forgiveness often becomes a cruel torture, because it remains out of reach for most ordinary human beings. Folk wisdom recognizes that to forgive is divine. And even divine forgiveness, in most religious systems, is not unconditional. True forgiveness cannot be granted until the perpetrator has sought and earned it through confession, repentance, and restitution.“Genuine contrition in a perpetrator is a rare miracle. Fortunately, the survivor does not need to wait for it. Her healing depends on the discovery of restorative love in her own life; it does not require that this love be extended to the perpetrator.

Once the survivor has mourned the traumatic event, she may be surprised to discover how uninteresting the perpetrator has become to her and how little concern she feels for his fate.“(pages 189-190, Chapter 9, Remembrance and Mourning)

tl;dr: Forgiveness is not a requirement for healing. You can heal and move on without forgiveness.

It can also harm you and it should never be demanded of you.

And you certainly don’t owe forgiveness to anyone.

This is mostly about maladaptive daydreaming but there’s a part I really want people on this site to pay attention to, particularly young people who are confused about fiction.

In 2002, an Israeli trauma clinician named Eli Somer noticed that six survivors of abuse in his care had something in common.

To escape their memories and their emotional pain, each would retreat into an elaborate inner fantasy world for up to eight hours at a time.

Some imagined an idealised version of themselves living a perfect life. Others created entire friendships or romantic relationships in their heads. While one man pictured himself fighting in a guerrilla war, another conjured up football and basketball matches in which he displayed his athletic prowess.

Their plotlines often involved themes of captivity, escape and rescue – being chained up in a dungeon, for instance, or leading a prisoners’ revolt.

My mother sent me this article because it reminded her of me. I saw why immediately. Even as early as age 5 I remember having elaborate fantasies about stuff like that. Being captured, escaping, adventures, scary things, torture. My first fanfic was literally about an Oddworld OC being tortured and killed. I was 7 when I wrote it. I talked to my mom a bit how a lot of people like me (abused, disabled, different) absolutely have grown up with fictional characters and stories as our reference for experiences, as the way we can try to make sense of our lives and the things that have happened to us. There’s a reason I feel more at home and with family when watching a favorite animated show with all the characters I love so much than in a big group of my actual family. Through these characters I was able to not only survive everything the real world threw at me, but learn very valuable things about myself, dissect my own experiences and feelings, even if at a younger age I wasn’t aware that that’s what I was doing. That’s the beauty of fictional characters. They really allow us the safety to go scary places with them. Even if that place is morally horrifying.

A lot of us survivors explore these kinds of themes. Dark things, unpleasant things.

Just keep that in mind before you get too deep into the purity culture of this site that states that anything dangerous, dark, or twisted being explored in fiction is worthy of, uh, telling that person to kill themselves.

Most of the time, you’re telling a survivor that it would have been better for them to have died than to have survived their trauma, and that’s really dangerous considering most of us struggle with suicidal ideation in the first place.

Not all of us like to deny the darkness that we came from. There is nothing wrong with that.

fuck, i spent so much of my childhood daydreaming badass adventures. and yeah, they were bloody and dark as hell.

my first attempt at a novel was about a disabled man named thorn who was imprisoned at the heart of a dystopic city and could act only through computers; he called himself thorn because the people that left him there called him the thorn in their side, and they’d made him forget where he came from, his name and everything. the antagonist and love interest was a woman with several robot prostheses who worked with a rebel group to sabotage the city, not knowing the ‘comptroller’ they hated so much was just as much a prisoner as they were. when she finally stopped trying to kill him and decided to rescue him, he died a few hours later, unable to survive without his machines.

melodramatic, i know, but i was twelve.

looking back now, as an adult, i’m a little disturbed by how lovingly i described the violence. but i needed it, apparently. it made me feel better, going into my dark world and writing about this pale, wormlike man and his sicknesses, and the cruel things he did without understanding them, because he was a great big obvious metaphor for dissociation. and it was cathartic writing the woman – i can’t remember what i named her, something very cyberpunk and edgy i’m sure, like razor or cobalt – just mowing through crowds of company grunts with a bewildering assortment of heavy weapons. i wasn’t even allowed to watch pg-13 movies yet but i sure did like to talk about guts.

it all felt more real than the real world, sometimes, because the real world was where i wore a rigid mask of neurotypicality and gender and so on.

this makes me think of a convo with a friend the other night about seeking validation that harm occurred from the one(s) who harmed you (in this case i was talking about my relationship with my parents, mostly my mother.)

“seeking validation that harm occurred from the one(s) who harmed you.”

wow. yes

Because traumatized people often have trouble sensing what is going on in their bodies, they lack a nuanced response to frustration. They either react to stress by becoming “spaced out” or with excessive anger. Whatever their response, they often can’t tell what is upsetting them. This failure to be in touch with their bodies contributes to their well-documented lack of self-protection and high rates of revictimization and also to their remarkable difficulties feeling pleasure, sensuality, and having a sense of meaning. People with alexithymia can get better only by learning to recognize the relationship between their physical sensations and their emotions, much as colorblind people can only enter the world of color by learning to distinguish and appreciate shades of gray.